As Singapore fights to keep narcotic abuse off its shores, one battleground is starting to look bleak — a startling rise in young teen addicts.

GENERATION HIGH

A final-year project by

Matthew Loh, Elgin Chong, Emmanuel Phua and Osmond Chia

Photos by: Elgin Chong, Graphics by: Osmond Chia

A final-year project by

Matthew Loh, Elgin Chong, Emmanuel Phua and Osmond Chia

This website is currently being displayed for larger monitors.

FOREWORD

Where the Republic once battled a meteoric rise in heroin and cannabis addictions in the 1970s and 1980s, and then the scourge of ecstasy in the 1990s, it now sees one of the world’s lowest rates of drug abuse.

That decline is largely associated with Singapore’s notoriously hard stance on drugs, with long-term imprisonment for addicts, the death penalty for traffickers and a controversial law that assumes a trafficker is guilty until proven innocent.

It seems to have worked; annual drug-related arrests here have almost halved over the last three decades.

But statistics show that a small demographic of abusers has defied this trend. Teen drug arrests nearly doubled from 2014 to 2019, despite drug abuse tapering off among most Singaporean adults.

Underage youths who persist in using drugs also grow into the young adult age range, currently Singapore’s highest contributor to drug arrests every year.

When the four of us began our investigation, we were skeptical. Drug addiction was a distant problem to us, confined in our minds to dysfunctional families or the usual misfits.

Our interviews revealed an issue much closer to home. Former gangsters described commonly seeing 13-year-olds high on meth; addicts recounted dealing in broad daylight at crowded shopping malls; teenagers who came from families just like ours spoke of how they spiralled into addiction.

Most of our project is told through the story of Joshua, a former teenage drug abuser whose struggle with addiction hits many of the beats highlighted in our findings.

All of the roughly 40 youth workers we interviewed said that the teen drug situation, though still not dire, has grown enough in the last five years to become a primary concern.

They highlighted a fundamental shift in the way Singaporean youths view narcotics — a cultural change that if left unchecked, will herald the start of a new generation more willing to return to drugs.

There is reason to believe that Singapore is winning its war on drugs.

This project follows one boy's descent into drug addiction and his subsequent rehabilitation and recovery.

Click on one of these links to jump to a story, or scroll down to begin...

*Names have been changed to protect offenders' identities

An invasion of new, cheap substances and growing positive sentiment towards drugs has youth workers on edge.

THE NEXT FRONTLINE

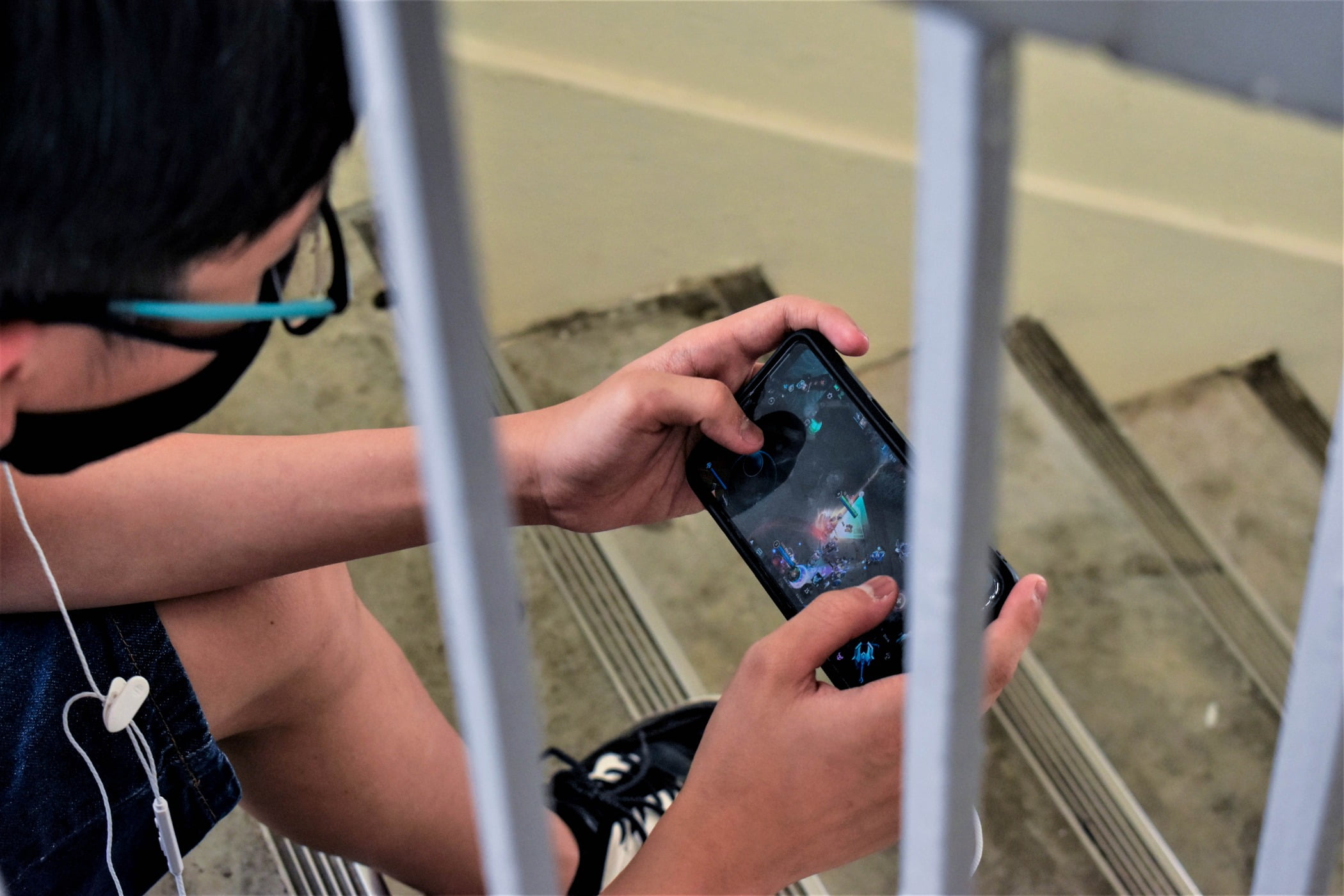

Joshua, then-17, was trying weed for the first time. He and his secondary schoolmates had met to design a class T-shirt. An hour later, they were in a friend’s bedroom rolling joints.

It was almost picturesque — leaning out the window, fingers wrapped around the smouldering synthetic leaves, gentle smoke swirling from his lips and into the Saturday afternoon sun.

They called it Butterfly. A man-made drug that mimics the effects of marijuana, it comes cheaper than regular weed and smells just like tobacco when smoked.

Better yet, it was “a hundred times” stronger than the real thing, said Joshua.

“You could easily make friends with this stuff. All of my friends wanted to try it, because it was so popular in the West,” he said. He declined to provide his full name for the sake of his family’s privacy.

Now a 21-year-old art student, he personally knew at least 50 secondary schoolmates who took drugs.

Illegal drug abuse among Singapore’s under-21 youths has surged in the last seven to eight years, according to youth workers and experts.

More than 30 interviewed social workers, counsellors and youth organisation heads warned of a steady increase in teenage drug addiction cases over the last five years.

Their foremost concerns lie largely with a growing acceptance of drugs among youths and the influx of cheaper, unidentified drug variants into Singapore.

One puff, and he was high.

While his family slept, Joshua

often secretly smoked Butterfly

at his living room window.

For young Joshua, that Saturday afternoon at his friend’s house sparked a year-long addiction. Craving more, he met a dealer at a party and started spending up to S$200 a month on drugs.

He spent the bulk of the money, which he often stole from his parents, on Butterfly, just one of the many new drug variants that experts noted have been taking the younger crowd by storm.

NEW PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS ON THE RISE

Former young addicts and dealers said that such drug types are usually cheaper yet more potent than their counterparts on the market.

Most of all, they had a street reputation of allowing users to evade detection from urine tests, though CNB said it has enacted countermeasures to this.

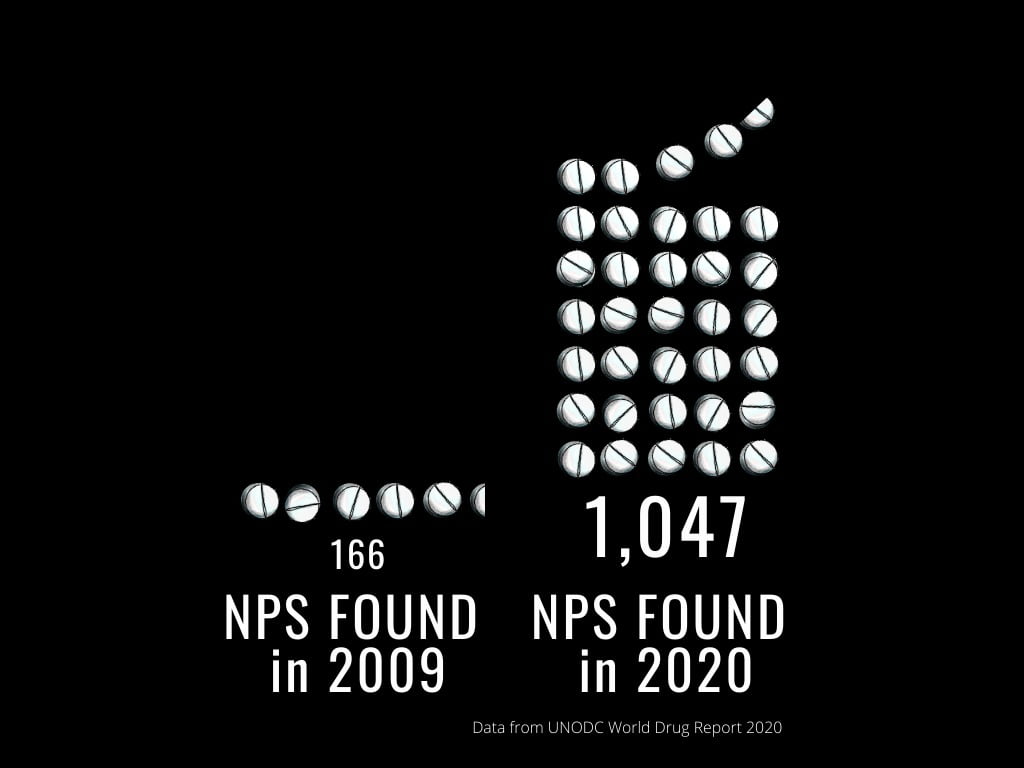

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) dubs these narcotics new psychoactive substances, a broad term describing any form of harmful drug that is not one of the more than 200 internationally controlled narcotics like cocaine, heroin or ecstasy.

UNODC reports that the first new psychoactive substances emerged in Europe around 2004, gaining popularity as “legal highs” and “designer drugs” that replicated the effects of drugs but were not yet labelled as illicit substances.

As these drugs moved to the rest of the world and authorities clamped down on specific breeds, the rogue chemists manufacturing them would alter their formulas to spawn more uncategorised narcotics.

The result has been hundreds of novel drug variants, including synthetic cannabis like Joshua’s Butterfly, flooding the global narcotics market. Their numbers have swelled in the last decade; 1,047 different new psychoactive substances were detected by 2020, up from 166 in 2009, according to the latest UNODC World Drug report.

Such substances have found their way into Singapore as well. UNODC’s Early Warning Advisory highlighted that 511 new psychoactive substances were discovered in East and South East Asia alone, and at least a quarter of these have been reported in Singapore.

Since 2018, new psychoactive substances have become one of Singapore’s top three most commonly abused drugs, according to CNB’s annual report in February 2021.

The cheap prices for some of these drugs have made them especially popular among young teens, said social workers and drug rehab staff.

“Drugs are definitely more accessible today. We have cases where children bring drugs to school and share, and do drugs in the toilet,” said Ms Lee Hwee Nah, assistant director at Singapore Children’s Society’s youth service centre, which works with approximately 100 youths per year.

“There are also a lot of peddlers out there, who are older folks, who will approach the youths. They know who to target,” she said.

Drug abuse has become the chief concern in the past year for Mr Ong Teck Chye, head of outreach and residential services at Boys’ Town, a charity that provides hostel stay and programmes to at-risk males under 25. Its outreach branch, YouthReach, works with more than 300 youths on the street per year.

“YouthReach has seen an increase in the number of youths who have been exposed to new psychoactive substances in the last five years,” said Mr Ong, who has been running YouthReach for six years.

Likewise, secondary school counsellor Mullai Pushpanathan handled 11 drug abuse cases in 2019, involving male students aged between 15 to 17 from her school. It was the first time she had encountered youth drug cases in her 11-year school counselling career.

“It was a shocking revelation… All 11 of them took new psychoactive substances,” she said.

Ms Mullai said that no further drug abuse cases were brought to her in 2020, but thinks this was likely because students and teachers met less frequently during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Still, she believes that 2019’s sudden emergence of drug cases indicates a more widespread yet unsurfaced addiction issue among her students.

“These youths are smart enough to fool the system, so they consume these drugs because they know it can only be detected by taking a hair sample analysis,” she added.

New psychoactive substances are notorious for being able to evade detection from standard forensic tests, because of the sheer number of new variants entering the market every year. Some are also known to pass from the human body quickly, leaving no trace in the user’s urine or blood.

CNB communications director Mr Sng said that the bureau has been using hair sample tests since 2013 as it can detect drug abuse over a longer time span than urine tests.

Still, the untraceable reputation of these substances was exactly what made them so attractive to Joshua and five other interviewed young ex-addicts.

Joshua was always certain he would not be charged if he was caught, as he believed that Butterfly was still not categorised by the authorities.

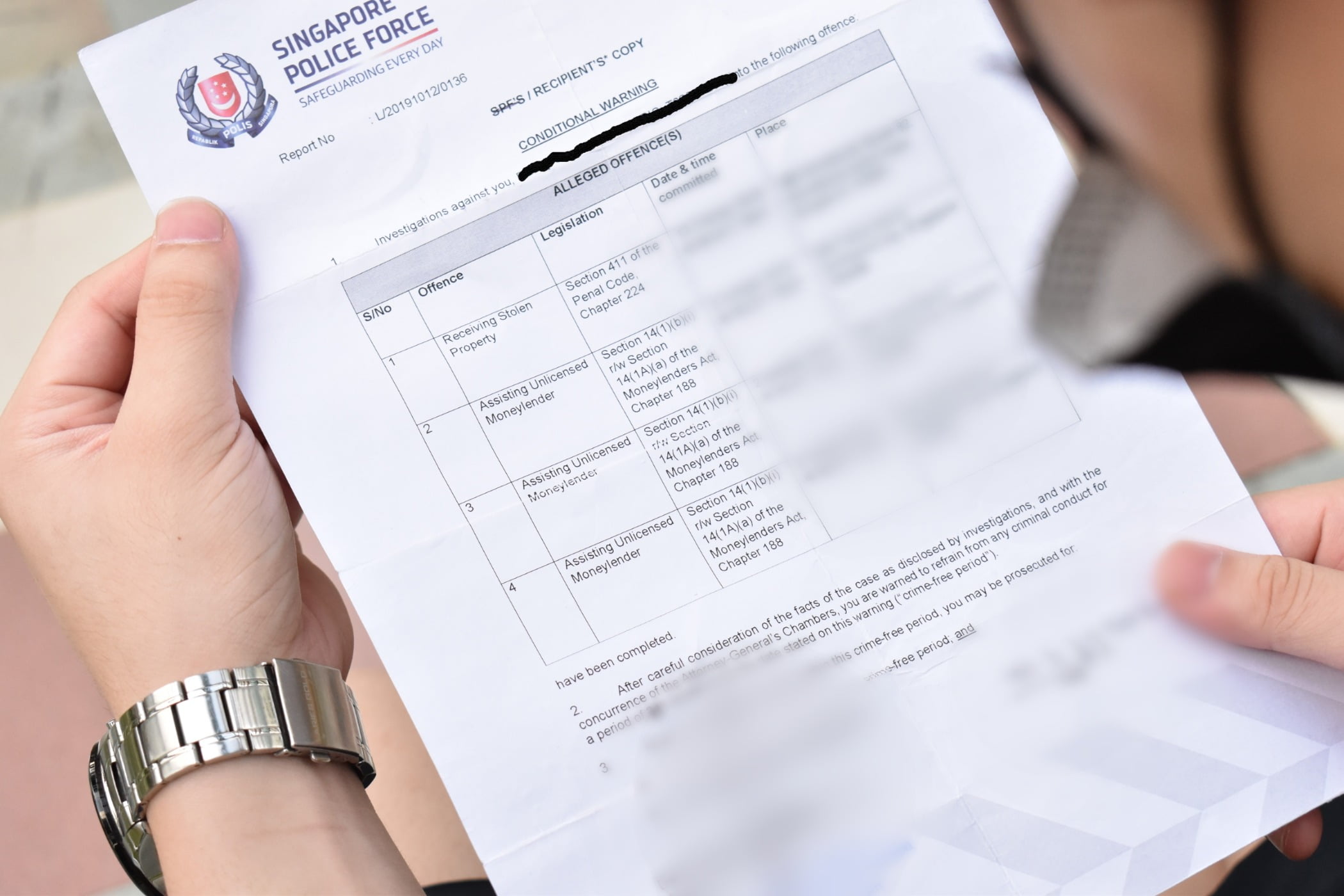

Like him, former addict and dealer Saul*, now a 21-year-old polytechnic student, was never charged for consuming drugs despite undergoing a urine test when he was caught for weapon possession.

At the time, he regularly consumed a synthetic cannabis variant called K4, which he peddled in school since he was in Secondary 1.

Saul said he took K4 shortly before his urine test but nothing was flagged.

He and Joshua described their experience with synthetic cannabis the same way — it “ruined” or “destroyed” their brains.

They reported several intense side effects from their use of new psychoactive substances. Joshua experienced regular head pains after consuming Butterfly, and remembers blacking out several times after puffing the drug. He also often felt severe nausea.

“I gained a lot of weight, and my temperament was horrible. I don’t know why, but it affected my mood. I got angry easily, my mind felt sluggish, I couldn’t think properly all the time,” he said.

Before selling to friends, Saul would sample each batch of K4 to ensure it was safe to consume, but just like Joshua, he was never certain of what was in the man-made weed.

“I knew I was pretty much risking my life every time I took K4. That was how potent it was,” said Saul.

The lack of information surrounding new psychoactive substances is precisely what makes them so dangerous, said Dr Ong Mei Ching, senior forensic scientist at the Illicit Drugs Laboratory of the Health Sciences Authority (HSA), which analyses drug seizures submitted by enforcement agencies.

New psychoactive substances produce side effects similar to traditional drugs like cannabis and meth. Abusers frequently are unaware of what they are consuming, which belies the danger of these narcotics, said Dr Ong.

“A person may think he is taking LSD, but they might not know that it could actually be a totally different drug which is more potent,” she said.

A 2019 review article in the Mental Health Clinician journal has linked synthetic cannabinoid usage to a range of severe toxicities that cause health complications including cardiac arrest, irregular heartbeat, psychosis, seizures, kidney injuries and internal bleeding in the skull or brain.

In Singapore, there have been four new psychoactive substance-related deaths since 2016, two of which involved male teens aged 17 and 19, according to a case report by HSA.

Both teens died from drug toxicity, or a type of drug poisoning — one from a variant of LSD and another from synthetic weed.

“This is the risk,” said Ms Lee. “Many of these youths have the misconception that new psychoactive substances are less harmful to the body, when we know that they can actually be equally as harmful as other drugs.”

CRACKING DOWN ON NEW PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES

Like 60 other countries that have implemented legal responses to these drug breeds, Singapore has updated its Misuse of Drugs Act since 2010 to cover individual new psychoactive substances and their common chemical properties, allowing law enforcement to take action against these drugs.

The Ministry of Home Affairs also announced in March that it would amend the Act this year to regulate new psychoactive substances “based on their potential to produce a psychoactive effect”.

Arrests have started taking place in recent years. CNB reported that across all age groups, 414 drug abusers were nabbed for consumption of new psychoactive substances in 2019, a drastic increase from just one arrest in 2017. Arrests fell to 282 in 2020 as part of an overall dip in drug arrest rates amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

But some youth workers remain concerned about youths who have fallen through the cracks and continue to abuse drugs while undetected.

Mr Joel Shashikumar, head of Boys’ Town’s Therapeutic Group Home, which provides intensive therapeutic treatment to teenage boys with significant trauma or disruption in their lives, feels that it is a mammoth task for enforcement agencies to comb both the streets and the cyberworld to track down drugs purchased by youths.

Young addicts often use innocuous names for synthetic drugs like Butterfly, Magic Mushrooms and Spice, with no clear lines drawn between different drug variants.

“There will always be new psychoactive substances that are still not classified being sold online, and nobody will be able to keep track of every youth that is going to buy these drugs,” said Mr Shashikumar, who has been working with youths for nine years.

“It is harder to reach out to those youths who have not been picked up by the system, as they are the ones that are possibly buying drugs and smart enough to cover their tracks,” he added.

Getting caught for new psychoactive substances was unheard of for Eddie*, 17, who joined a gang when he was 13. His gang leader trafficked drugs and regularly supplied him and his friends with synthetic cannabis.

“About 40 per cent of my social circle used synthetics. None of them were caught, including myself,” said the ITE student, who currently studies mechatronics.

CNB communications director Mr Sng said that drug syndicates have become increasingly sophisticated and continue to alter chemical structures of existing new psychoactive substances and controlled drugs to avoid detection.

Senior forensic scientist Dr Ong said that forensic teams at the Illicit Drugs Laboratory typically take at least two weeks to identify new psychoactive substances — more than three times longer than traditional drugs.

“It is challenging for us at the lab, because of the number of techniques as well as the amount of effort required,” said Dr Ong, who has worked at HSA for 10 years. Sometimes, her lab can receive up to 100 such samples a month from CNB.

And new psychoactive substances can take a wide range of forms, be it plant material, tobacco, liquids or pills, she added.

Dr Ong said: “The drug market is rapidly evolving, so what appeared two or three years ago may not be in trend now. Our analytical methods need to be constantly reviewed and enhanced to keep up.”

Double-click to edit text

As enforcement agencies grapple with the deluge of new drugs in Singapore, social workers also describe a hard-fought battle against a snowballing attitude of acceptance towards drugs among youths here.

Ms Janet Wee, a former senior drug counsellor at the Singapore Anti-Narcotics Association (Sana) said that the youths she works with often seem apathetic about the adverse effects of drugs.

“Some of them told me that ‘you only live once’ so you will never know if you don’t try,” said Ms Wee, who worked at Sana for six years before she became managing director of Acorn Quest, a firm that provides counselling services for former offenders including teens who started taking drugs when they were as young as 10.

Mr Ong from Boys’ Town noted that while drug abuse has always been present in Singapore, there is now a common misunderstanding among teens that drugs are harmless.

“There is a mindset shift and youths are now more open to trying drugs, thinking it can’t be that bad since the Western countries have legalised marijuana,” he said, referring to the legalisation of marijuana for recreational use in Canada and 15 American states.

Ms Lee of the Singapore Children’s Society said her centre runs educational programmes that dispel myths surrounding new psychoactive substances and other drugs.

"Many of our Singaporean youths, if they read overseas articles or platforms, they will challenge us, and say that it’s very acceptable to abuse drugs overseas. They will start to ask why Singapore is so old fashioned,” she said.

CNB communications director Mr Sng said there is insufficient scientific evidence to support the medical benefits of cannabis in Singapore. He added that the bureau is concerned about pro-cannabis proponents on social media.

“In some people’s minds, drugs are not a problem in Singapore, because they seem so distant. Our drug arrest rate is a tiny percentage of the total population,” he said. “But drugs are still a very serious issue here.”

GROWING ACCEPTANCE OF DRUGS

GOING OFF THE GRID

Months into his drug addiction, Joshua got bolder. He began smoking Butterfly in public spaces during the day, convinced that no one would notice as long as he played it cool.

“The most dangerous place turned out to actually be the safest place,” he said.

His strategy worked for the most part. Joshua’s parents never caught him in the act of smoking Butterfly, even when he used it in their home. Neither did the authorities. His brother, two years younger than him, knew about his addiction but would often cover for him.

Saul, who sold over S$10,000 worth of drugs in his secondary school days, would regularly deal synthetic cannabis in public and conceal the product in a parcel so as to not arouse suspicion.

“You cannot be scared, it’ll give you away and you’ll get caught. So I always got my friends to accompany me when I was making a deal,” he said. Saul always ensured that none of these friends knew his true agenda. He would sneak off during group outings at the mall to make a quick deal.

School counsellor Ms Mullai, who has worked in secondary schools for more than a decade, said that youths are getting more resourceful and know how to use novel methods to give authorities the slip.

“Besides knowing different places where they can get these drugs, the youths would buy more so that they can resell them in smaller packets to fuel their drug habit,” she said.

Ms Lee from the Singapore Children’s Society spoke of how savvy at-risk youths have become with evading urine checks.

“They’re well-informed. We have youths who we require to go for frequent urine tests, maybe once every two weeks or so. They know if they take a drug today, how long it will take for it to not appear in a urine test. And so they try to use that timeframe,” she said, adding that some are unsuccessful because they can never be totally certain when the drugs will wear off.

In the end, Joshua was never caught by enforcement agencies, despite his cavalier demeanour with drugs in public.

“Back then, the thought of getting caught never crossed my mind. I think most youths don’t realise how dangerous it is,” he said.

His parents took more than a year to suspect that he was addicted to drugs. When they confronted him, he promised to stop but relapsed soon after.

In the end, it took nine months of isolation at a Christian halfway house for Joshua to finally wean himself off Butterfly.

“It was difficult to get out because once you know one guy, he would introduce you to his friends and you can start to grow your drug network,” he said.

An outdated belief surrounding drug abuse has parents missing the signs of addiction in their teens, say youth workers and experts.

BLIND SPOTS

But it smelled just like tobacco.

When 17-year-old Joshua arrived home late and collapsed on his bed, bleary-eyed and unresponsive, his suspecting father Mr Lim* rummaged through his backpack.

The crinkling, brown leaves he found inside smelled just like tobacco, but he knew it was cannabis. And he knew then that he had been fooled by his son.

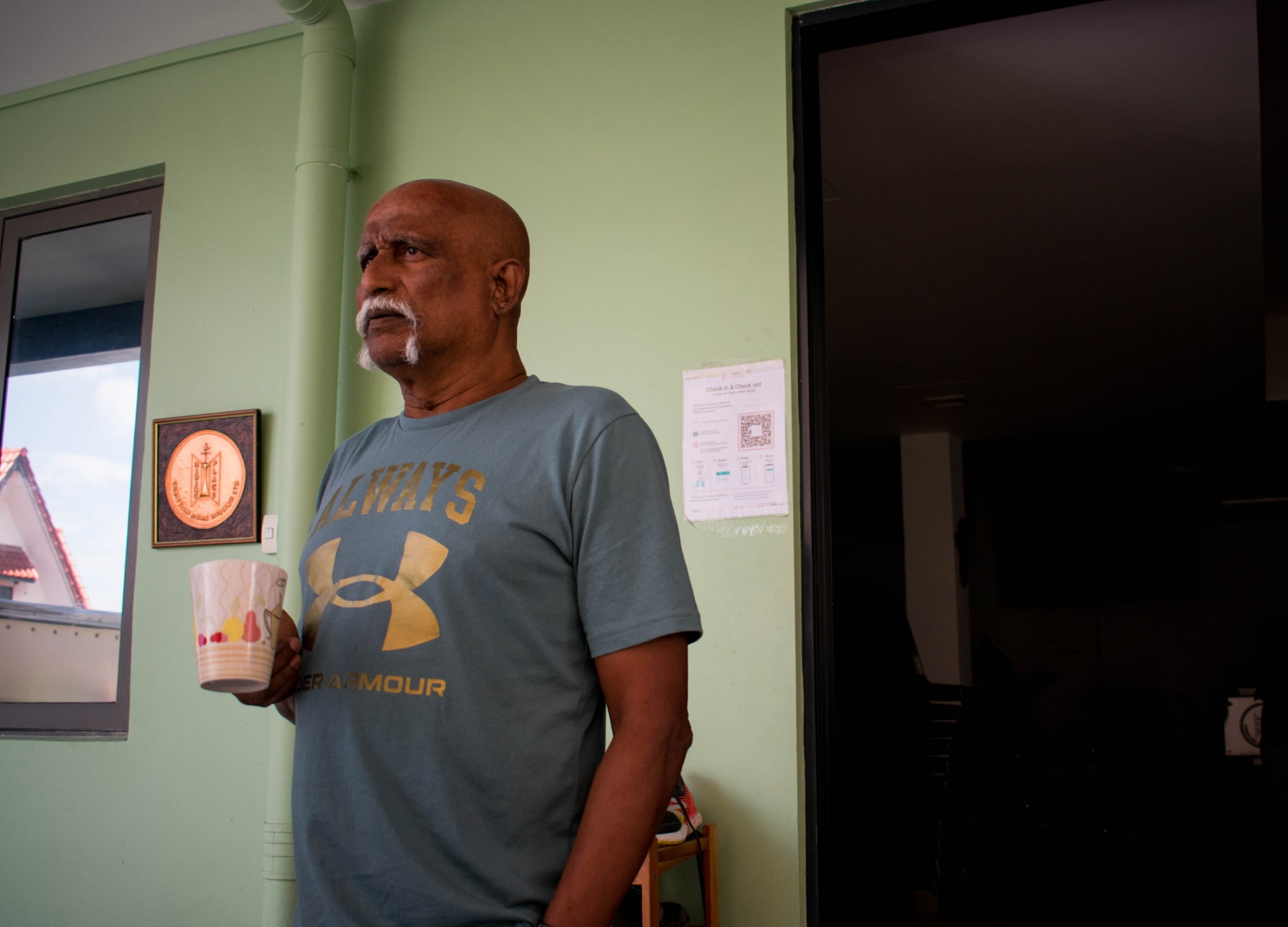

“I spent my life surrounded by drug dealers… I saw friends bury their sons because of drug abuse. I was afraid to lose him,” said Mr Lim, an ex-addict in his 50s who asked to remain anonymous for his family’s privacy.

By the time he discovered Joshua’s stash that day, the boy had already been an addict for a year.

The teen would often ask his parents — an accountant and a music teacher — for money beyond his allowances, claiming he needed it for small expenses like food or transport. Sometimes, cash went missing in the house. His parents noticed him becoming aloof; he was usually in a daze and spent most of his time at home asleep.

“But no parent would expect this of their child. That they would fall to drugs,” said Mr Lim.

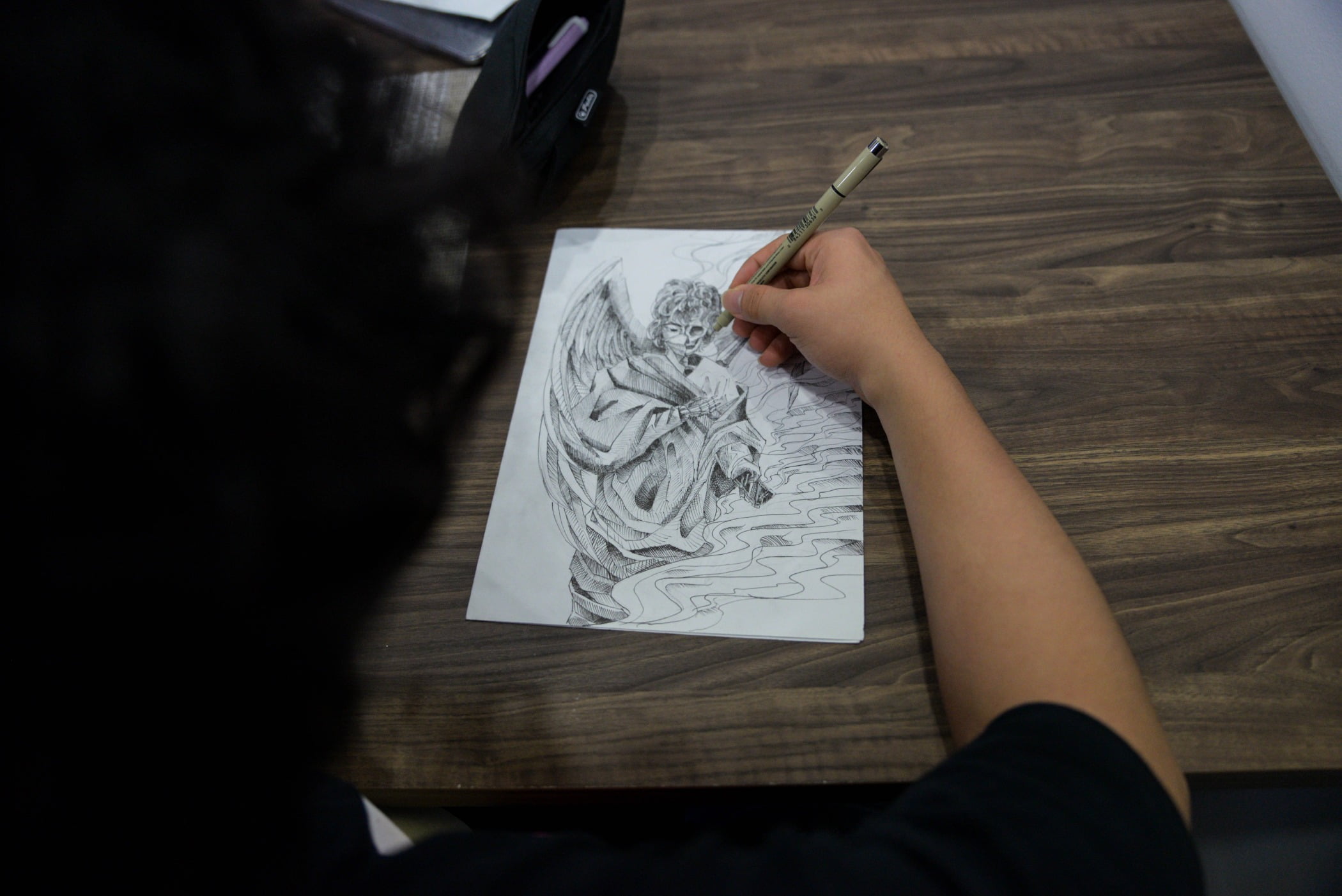

Joshua (pictured) had picked up a synthetic cannabis addiction when he was in secondary school and continued abusing the drug during his time as a tertiary fine arts student.

Joshua fits a demographic of drug abuse among youths that has shifted drastically in the last five years. Though underage addicts in past decades often came from poor or gang-related backgrounds, the average profile of a young Singaporean drug abuser has recently expanded to encompass wealthier families, said experts and authorities.

But they said the stereotype that drug abuse is limited to poor or broken families has become a crippling blind spot for many parents or guardians, causing them to become unwary and unprepared for signs of drug addiction in their children.

At least 10 youth workers and experts specifically highlighted as much as a 50 per cent increase in the number of drug abuse cases from middle and upper-class family backgrounds.

Joshua’s parents, both staunch Catholics, describe themselves as middle-income earners. During Joshua’s year of taking drugs, Mr Lim held a stable finance job in the aviation industry, while Mrs Lim taught music at a private institution and gave lessons in their four-room flat.

Their early years of courtship were marred by Mr Lim’s marijuana addiction, which he took years to kick. After starting a family when he was drug-free, he would often lecture his two sons on the dangers of drugs and to stay away from them.

Mr Sng Chern Hong, CNB communications director

For years, it seemed to have been enough. Joshua and his younger brother were well-behaved, scored decently in school and regularly attended church.

And so for months, Joshua’s synthetic drug addiction slipped past even an ex-addict like Mr Lim.

Communications director for the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) Sng Chern Hong said that the demographic of young drug abusers has changed, from one of lower socioeconomic status to a wider spectrum of backgrounds.

“We now see abusers from good backgrounds, from families with good incomes,” he said. “We need to avoid this stereotype that drugs only affect those who are down and out.”

Ms Chrysan Chiang, a social worker at halfway house The New Charis Mission, said that this rise in youth drug abuse among middle-class Singaporeans could possibly be related to lower child supervision in families where both parents are working.

The New Charis Mission home has seen an upward trend of at-risk youths who come from middle and upper-middle class families — a stark contrast from the narrative in the past.

“Drug abusers used to often come from the lower strata of society, but now, there are youths coming from wealthier families because there is not much supervision going on," said Ms Chiang, who works closely with about 15 at-risk youths a year.

Similarly, Mr Wilson Peh, a social worker who works with about 100 youths per year under charity organisation Youth Guidance Outreach Services, estimated that 60 per cent of the cases he handles nowadays come from middle-class or wealthier families, compared to 40 per cent from five years ago.

“Now we are starting to see a lot more kids coming from families that aren’t struggling financially. More are coming with psychological issues, social problems that manifest in at-risk behaviour,” he said.

He also believes that families are now pressured to have both parents in the workforce because of rising standards of living in Singapore, and that this would make it more difficult for parents to supervise their children.

According to the latest statistics from the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF), dual-income families made up 65.6 per cent of Singaporean households with at least one child aged below 21 in 2015, up from 45.9 per cent in 2000.

“The parents are usually very shocked when they find out that their boy has been caught for something because they don’t know that this is happening,” said Mr Peh.

“Parents will tell me that the standard of living is very high and there is no time to accompany their child.”

On the morning that Joshua’s father found the stash of synthetic weed, the boy tried to lie that the leaves were tobacco from India after being confronted. When Mr Lim said he would smoke them to judge for himself, Joshua conceded that they were drugs.

Mr Lim admitted he and his wife could have spent more time with their sons.

“That was the no-good thing about us. We were always busy pursuing our careers, and when we were not busy with work, we were preoccupied with our own nonsense,” he said.

Every night, Joshua, now a 21-year-old art student, would lean out his living room window, puffing a joint of synthetic cannabis while his parents slept soundly in the next room. Smoking drugs at home became such a norm to him that he rarely bothered to step out of the house whenever he felt the urge to use the drug.

“You are put in this dead state where you are just so lazy to even walk out of your house, so you would rather just do it at home,” said Joshua.

Looking back, his parents realised that signs of his addiction had already been visible before they caught him red-handed.

Mr Lim once discovered that Joshua snuck out of their house late at night, and found him at a void deck downstairs with a school friend. They were smoking synthetic cannabis, but managed to hide it from Joshua’s father.

Mr Lim demanded to look through Joshua’s phone, and saw text messages discussing synthetic cannabis.

“I already had my suspicions, but I was just hoping not to be right,” said Mr Lim.

Ms Chrysan Chiang, social worker

at The New Charis Mission

STEREOTYPES CATCHING FAMILIES OFF GUARD

Experts and youth workers also noted that wealthier parents tend to look over their child’s misdeeds because they assume that their children would not get in trouble.

Mr Josephus Tan, a former delinquent who is now a criminal lawyer and the managing director of Invictus Law Corporation, said the common idea that drug abusers only come from poor or broken families has become a dangerous mindset among parents.

In recent years, Mr Tan, who is an advisor to the Youth Court and has worked with many cases of drug abuse among youths, has noticed significantly more cases where teenagers from wealthier families were caught for drug offences.

“You realise that our profile of young drug abusers these days, their parents are professionals, white collar workers, educated to an extent. Financially they are not too bad, they can even stay in condominiums,” said Mr Tan.

“Their kids attend good schools. They might not be from Normal (Technical), they might be from express streams or branded schools.

“I have parents saying: ‘My kids can’t be doing drugs. Please! Drugs are for gangsters, for people who stay in HDBs. They stay in old neighbourhoods like Redhill, we stay (on Holland Road). My boy studies in a top school’,” he said.

“It is exactly this stereotype of the past that endangers you, because it creates a blind spot. Because parents think that they do not have to worry just because their kids come from a good background.

Dr Razwana Begum, head of the Singapore University of Social Sciences’ Public Safety and Security Programme, said that social class and education level no longer play a factor into the likelihood of youths experimenting with drugs.

“I think the typical image of drug users has changed. It's not necessarily that they are not educated, dropped out of school or hanging out in the void decks,” said Dr Razwana, who was also a probation officer with MSF from 1999 to 2018.

Easily accessible online information about the legalisation of drugs in the West has played a part in this, she said.

"They are trying to push this out-of-boundary marker. They're trying to figure out why it's allowed in other countries and why it's not allowed in ours."

She warned of the danger that these youths put themselves in by experimenting with drugs like new psychoactive substances.

“They may look at it as a one-off thing, that they are just trying it for fun. But new psychoactive substances change all the time so there is no way you would know what harmful ingredients are in there, and how dependent you will be on it,” she said.

“Before you know, you may even become hooked on it.”

Fighting addiction was an uphill battle for Joshua, who initially pledged to stay away from drugs after his father caught him at the void deck on that late night.

His parents, though bewildered by the idea of their son taking drugs, did not turn him in to the authorities for fear of exposing him to other drug abusers.

Both fervently religious, they instead believed that Joshua should improve his life spiritually, and made him attend a church retreat.

But a few weeks later, Joshua started reconnecting with old friends from his drug network and his craving for synthetic cannabis spiralled out of control again.

This time, he made sure to consume the drug when he was away from home, while at nightclubs and chalets.

Then came the evening when he returned home stoned, unable to say anything to any of his family members, and fell into a deep slumber.

Discovering the synthetic weed in Joshua’s bag was the final straw for Mr Lim. He issued an ultimatum to Joshua — check into The Hiding Place, a Christian halfway house, or get thrown to the streets.

“It was the lowest period of our lives,” he said.

FAMILY STILL CRUCIAL

Mr Lim is not the only ex-addict to be blindsided by drug abuse in their family.

Madam Kasmawati Kali Ubi, a 58-year-old health therapist and mother of two, warned how difficult it was for a former heroin addict like her to recognise drug abuse in her adult son, who stayed with her after his divorce in 2018.

Her son, Frank*, 34, is currently serving a detention at the Drug Rehabilitation Centre (DRC) after being caught for meth abuse last November.

He started abusing drugs in late 2019 during a bout of severe depression induced by his failed marriage.

While Frank initially was antisocial and locked himself in his room, Madam Kasmawati noticed over time that he suddenly became outgoing, which she attributed to the antidepressants he was taking.

In reality, he was on meth, a drug that induces the user with wakefulness and euphoria. When CNB officers came knocking on their door, she found out that Frank had purchased the drug online.

Muhammad Zulkarnaen Abdul Razak (L), rushed home when his mother, Madam Kasmawati (R) informed him about Frank’s situation. “I was so angry that I couldn't say anything,” said the 22-year-old, adding that he never once suspected his brother’s drug habit.

Frank (blurred) was detained in the DRC last December for consuming meth. He purchased the drug from a Telegram group introduced to him by his online friends.

Frank's bedroom has been vacant ever since his detention. "I don't want to get my hopes up, but I really hope he behaves in DRC so he can come home earlier," said Madam Kasmawati.

Frank's situation made Madam Kasmawati realise that she and her family needed to be more vigilant. Now, she tries to be engaged with her younger 22-year-old son’s social circle.

“Whenever I don’t know who my son is with and where they are, I can contact his friends. It gives me peace of mind knowing that he is not doing the wrong thing,” said she said.

Mr Ong Teck Chye, head of outreach and residential services at charity organisation Boys’ Town said that he and his staff regularly assess how parents spend time with their youths, as it is a factor that can gauge the possibility of delinquent behaviour.

The assessment team at Boys’ Town, which runs programmes for at-risk males under 25, evaluates the quality, not quantity, of family time spent, he said.

“For example, do the parents even know what topics to talk about? Do they have activities they enjoy together? Or is the time spent just nagging and complaining? Then that defeats the purpose because the youths will not listen,” said Mr Ong.

Dr Patrick Williams, an associate professor of sociology at Nanyang Technological University, suggested ways that parents can be more involved in their child’s activities without having to change what they are doing.

“If you go out to a restaurant, it’s very easy to see every person at a table, all the way down to two-year-olds, using a phone. Dad on the phone, mom on the phone, every kid has their own phone,” said Dr Williams, who also conducts research on youth subcultures and at-risk youths.

“You don’t have to be a cop and change what your child is doing… If your kid’s on one phone and you’re on your phone, why not get on one phone together? You are going to have much more insight into what your kid’s doing and what they find meaningful,” he added.

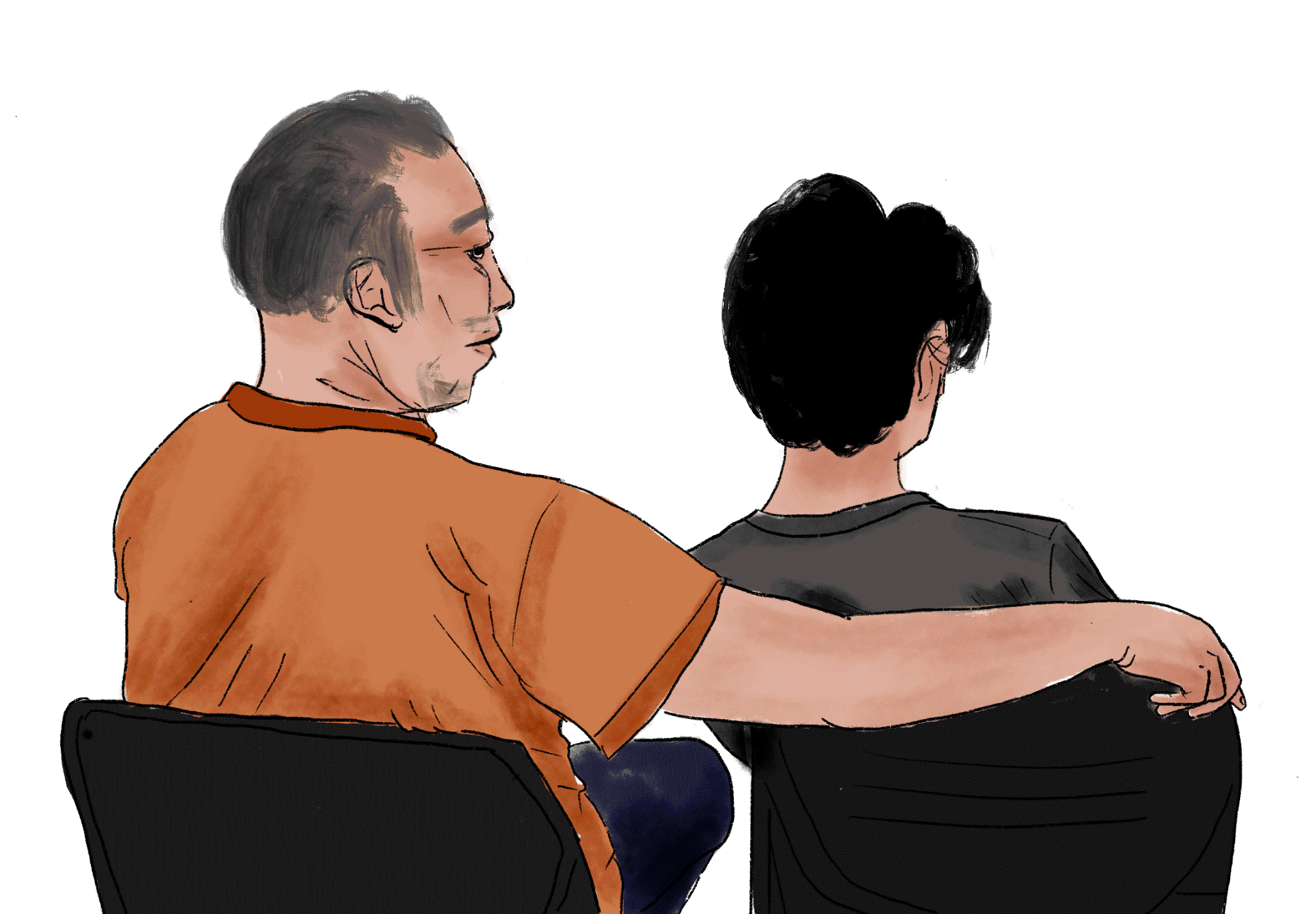

Mr Lim’s household started to prioritise family time since Joshua’s return from The Hiding Place, where he took nine months to finally kick his addiction.

As they sit in their living room, Mr Lim’s arm lies gently around Joshua’s shoulder, almost in an embrace. Joshua slouches comfortably in his chair, at ease and familiar with the parents he once shied away from.

Behind them is the family altar, where they pray together at 6am every morning and share their issues with one another.

“By doing this, it also gives Joshua’s lifestyle a fixed structure because we are still worried that he will relapse if he lives freely as if nothing happened,” said Mr Lim.

Since Joshua’s release, he has become selective with who he befriends, and makes it a point to stay away from anyone who smokes or drinks.

He also managed to dissuade his then-13-year-old brother from picking up a smoking habit.

“All our prayers were answered because Joshua managed to turn his life around,” said Mr Lim as he ruffled his son’s hair.

But they know he is one of the lucky ones.

Joshua’s initial plans for the day he checked into The Hiding Place were to buy drugs at his usual haunt in Paya Lebar. He later heard that CNB officers raided the area that same day, and his dealer was among those arrested.

Joshua said: “If my parents had not caught me early and sent me to The Hiding Place, I would have been there and dealt there.”

"It could have been me as well."

Singapore’s new emphasis on rehab gives social workers closer opportunities to tackle drug addiction.

UPROOTING

ADDICTION

Six days a week, residents at halfway house The Hiding Place spend hours tending to grassfields, kneading pastry dough or breaking scrap.

For then-17-year-old Joshua, who lived there for nine months in 2017 to kick a cannabis addiction, most days were spent plucking weeds in an 18,000 sq ft field — all by hand.

The result of his labour was never the point. Staff at the home assign chores to residents — mostly drug addicts — as a form of therapy that teaches them to listen to authority and adopt structure in their lives, said Mr Sart Sankaran, a senior staff member in charge of discipline. He is also the man who oversaw Joshua’s recovery.

The focus at The Hiding Place, he said, is not on punishing addicts but on “rebuilding the soul”.

That philosophy has started to show in the legal treatment of underage drug offenders here in the last decade, through a series of legislative changes in Singapore aimed at rehabilitative sentencing for drug addicts and young offenders.

Singapore still upholds stringent anti-trafficking laws, which hand out penalties including caning, life imprisonment or the death sentence, but youth workers and experts have noted a pivot by the Republic to help abusers overcome addiction instead of simply incarcerating them.

Among the more recent legislative changes, the Misuse of Drugs Act was amended in 2019 to allow drug offenders of any age to be sent to rehab centres instead of prison if they have no other concurrent offences.

That same year, the Children and Young Persons Act was changed to raise the youth offender age limit from 16 to 18, so that youth intervention programmes can cover older teens. The Community Rehabilitation Centre was also launched in 2015 as a step-down facility for under-21 drug offenders after they serve a short stint in the more regimental Drug Rehabilitation Centre.

Central Narcotics Bureau communications director Sng Chern Hong said: “There is this change not because we have gone softer, but over the years through research and studies, we realised that longer incarceration does not help with the reintegration of abusers.”

“If you are away for five years, it is difficult to reintegrate. What may help them is more treatment and rehab, to let them go back to the community.”

Mr Sng said that Singapore is still in the early days of its enhanced rehabilitation scheme, which commenced in 2019 after amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act.

“Of course there are people who relapse, but by and large, it is effective and we need some faith in our rehab programmes,” he added.

Executive director of Crossroads Prisons Ministry Singapore Paul Tan said the chance to return home and rehabilitate among family and community is crucial to a young offender’s recovery.

“The law is hard on those who have committed crimes and sell drugs. But it is more lenient on users, because they have been misled,” he said.

NEW EMPHASIS ON REHAB

In prison, addicts often expand their networks after mixing with other inmates who may be gang members or dealers, said Mr Tan, who provides counselling and talks for some 50 inmates and rehab patients per week — a third of whom are usually youths.

“It is like an underground business and (gangs) are always recruiting young people to join their trade. They find young people good with IT skills and tech to sell drugs on the internet, always looking for new people,” said Mr Tan, a former marijuana and morphine addict who bounced between prison and rehab in 1974 to 1979.

He said that rehabilitation gives addicts a better chance at long-term recovery through counselling, work assignments and hearing testimonies from former offenders.

“It is up to the individual. We can’t force someone to drink water, but we can put the water in front of them,” said Mr Tan.

Likewise, Mr Sart admits that some of The Hiding Place’s residents eventually return to their vices, but still believes rehabilitation is the best way to help addicts.

“There are cases not doing well, going in and out (of rehab), some up to five times. It all depends on the individual and how much they want to change,” said Mr Sart.

Youngsters are often uncooperative when they come to rehab, he said, but a common strategy used by social workers is to remind them of their family.

Whenever a youth enrols in The Hiding Place, Mr Sart would sit parent and child together in an interview room to discuss their road to recovery. Mothers would almost certainly cry, he said.

“It is very painful for a boy when they see their mother cry,” said Mr Sart. “She wants the best for you, and the most important thing is she loves you. Why did you turn like that?”

Dr Razwana Begum, a former probation officer for the Ministry of Social and Family Development from 1999 to 2018, said that family members also play an important part in rehabilitation programmes that allow youths to stay in the community, as they can teach them a sense of normalcy without drugs.

She cited the Youth Enhanced Supervision (YES) Scheme, a stay-out rehab programme introduced in 2015 for first-time drug abusers under 21.

It involves mostly counselling sessions and frequent monitoring through urine tests, and allows offenders to live at home with their families and be among other members of society.

“You know people around you are not taking drugs and doing bad things, so you try to conform,” said Dr Razwana, now a professor of Public Safety and Security at the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

“Why is it we all wear masks? Because if one person doesn’t wear one, everybody is looking at you.”

Mr Sart said that creating a healthy community for addicts is crucial at The Hiding Place, which moved last year from its facility on a farm on Jalan Lekar to a bungalow along Upper East Coast Road.

“These guys, they’re often ruffians. It is not easy for them to work with others. We try to create harmony between all of them,” he said.

He stays in with the residents to help establish a consistent culture of discipline and positivity in the halfway house, his practice for the past two decades.

While he has not seen a significant increase in drug abusers coming to The Hiding Place since the amended laws, he said addicts have been a constant since he started working there, and account for roughly 70 per cent of its residents.

Dr Razwana Begum, head of the Singapore University

of Social Sciences' Public Safety and Security Programme

Meanwhile, social worker Chrysan Chiang said more youths have recently enrolled into The New Charis Mission Residential Programme, making up a third of its total residents.

“This is a lot more compared to long ago,” said Ms Chiang, who has worked at the halfway house for 10 years.

“There is an increased awareness of such avenues of help. Previously, people usually filed a ‘BPC’ (Beyond Parental Control) and handed them to the authorities or let the kid be,” she said.

The organisation runs a one-year programme that allows residents to spend their daylight hours away from its premises at Jalan Ubi to be with their families after they complete a stay-in period of roughly six months.

The New Charis Mission is currently one of at least 12 halfway houses partnering with the Singapore Prison Service to help offenders return to society.

In 2019, Selarang Halfway House, the first Government-run facility providing aftercare support for prisoners, was launched to facilitate a gradual return to society for higher-risk ex-offenders.

Several homes are independently managed, like The Hiding Place, which Mr Sart said does not receive Government funding.

Some families choose to alternatively send their teenage addicts to rehabilitation programmes overseas like in Malaysia and Chiang Mai, Thailand, according to The Straits Times, which reported in 2015 that some clients were willing to pay up to S$21,200 a month.

The report also found that these foreign centres have seen a younger and wealthier client base in recent years.

REBUILDING THE SOUL

Each morning, Mr Sart oversees the halfway house’s routine of morning personal reflection time, bible studies and prayer sessions, before a long day of work therapy and counselling.

He remembers when Joshua first arrived at The Hiding Place, shaking from withdrawal symptoms. At first, Joshua, who did not provide his full name for his family’s privacy, hated the strict schedule imposed by the staff, and often showed up late for activities and work sessions.

Mr Sart is instantly recognisable with his signature Aviator sunglasses, a collection of cowboy hats and a white moustache that reaches down to his jowls. A whip hangs above his desk, which he insists is just for show. “I whip them with my tongue,” he laughed.

He dreaded Mr Sart, the man behind the laborious tasks whose thundering voice would descend upon the boy when he was uncooperative.

It took three months of work therapy and counselling for staff and other residents to break through to Joshua. At a group session one morning, he broke down in tears and finally shared about his struggle with drugs.

“Ever since that day, things were different for me,” said Joshua, who added that counselling at The Hiding Place helped him to reflect and realise his drug addiction was fuelled by a desire to belong.

As a young boy, he struggled to make friends, and drugs made him popular with some schoolmates.

Through work therapy, he learned to cope with loneliness and boredom in healthy ways.

Joshua noticed Mr Sart was softer with him and trusted him with more tasks during work therapy. And in turn, he grew to enjoy the discipline master’s company.

Mr Sart said that after that morning, Joshua started to focus on his work tasks diligently, a sign to staff that a resident was ready to return home. The teenager who once stayed up to smoke synthetic weed started spending his late nights studying so he could return to art school.

In 2018, the Hiding Place returned Joshua his mobile phone and he was free to leave.

It was a while before life at home returned to normal. In the initial weeks of Joshua’s release, his father was on edge, constantly paranoid that his son would relapse.

And drugs still lurked around the corner. Secondary school friends from his old network regularly asked to meet up, and Joshua was certain there would be alcohol, cigarettes and possibly drugs.

“It was so hard to say no at first. I thought I was close friends with them, but after I told them I stopped, they stopped contacting me,” he said.

He started being selective with his friends and chose not to hang out with people who smoked and drank excessively.

Joshua, who has been drug-free for four years, said: “I remember the week I went back to school, I had anxiety problems. I was away for so long and suddenly back in the open. There was a lot of temptation to get back to smoking.”

“I believe it’s all connected. If I do pick up drinking and smoking again, it’s like a spiral and I could go back down the same path.”

Till today, Joshua visits The Hiding Place every month to catch up with Mr Sart and the other staff, cycling for two hours each time from his home in Yio Chu Kang to the new Bedok facility.

Mr Sart remembers his parting words to Joshua when the teenager’s father picked him up from The Hiding Place. He kept it brief: “Press on, boy.”

In Joshua’s years as an addict, never once did he purchase drugs on the internet. Online drug deals left too much evidence, and he preferred face-to-face meetings, he said.

Youth workers are now seeing the opposite.

With its anonymity and unmatched accessibility, the online drug market is attracting local youth, unsettling

social workers on the ground.

The recent growth of Singapore’s online drug market has sparked alarm from youth workers, who observed signs of an undocumented wave of youngsters using the web to gain unbridled access to dangerous narcotics.

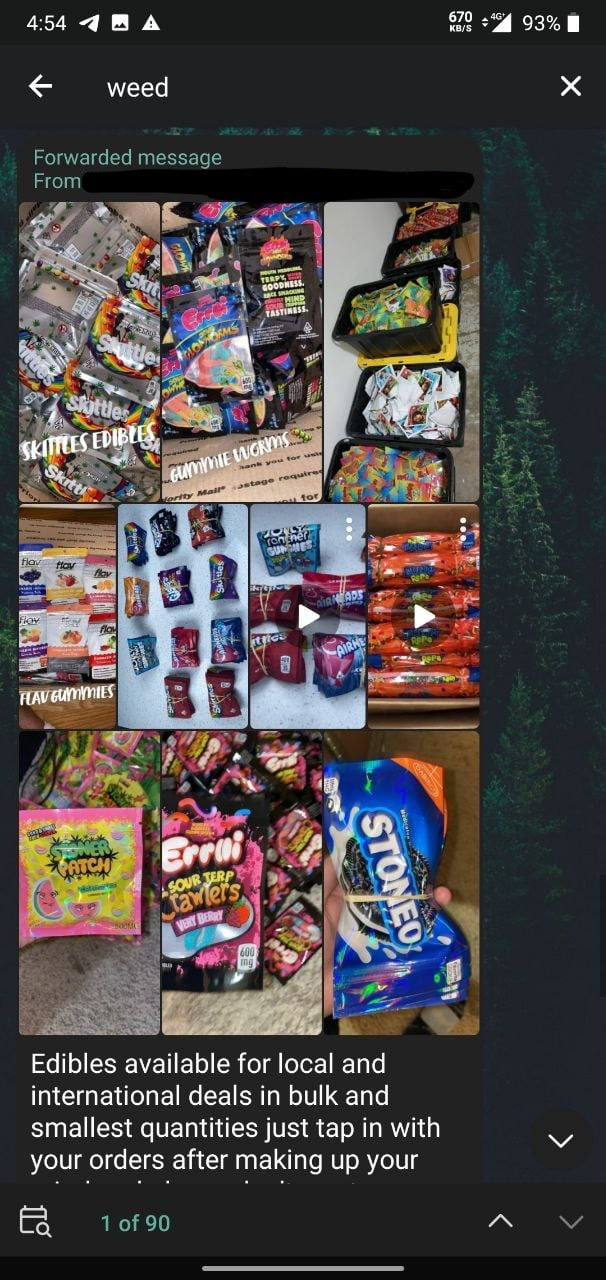

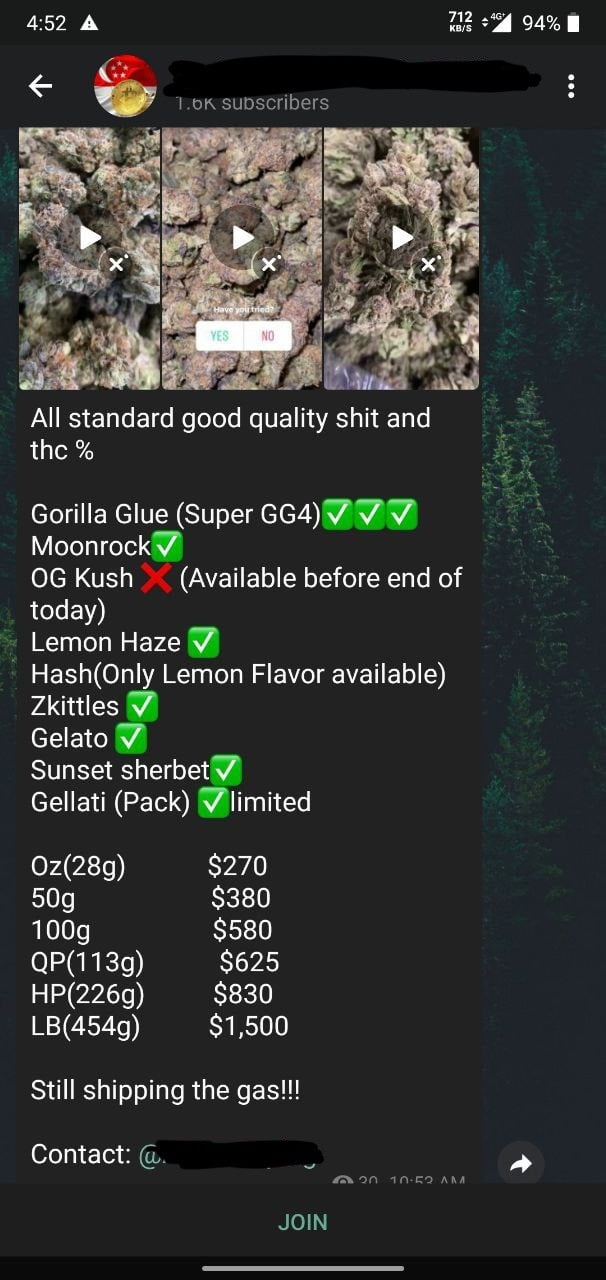

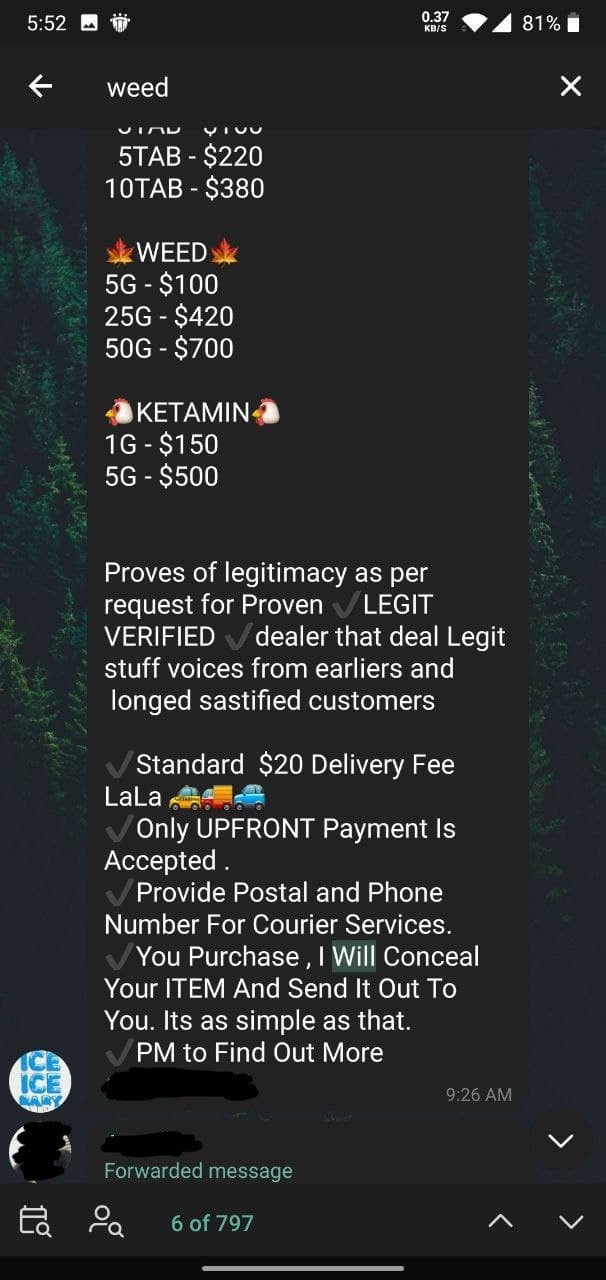

Over 20 interviewed counsellors, social workers and experts said they encountered recent cases of teenagers or tweens going online to purchase illegal drugs or join drug networks — something none of them saw five years ago. Many of these youths used legitimate social media, messaging and marketplace platforms, they noted.

This incursion, they also warned, has opened the drug world’s floodgates to Singapore’s youths, giving them the accessible means to anonymously trade narcotics that they would previously have needed street connections to procure.

Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) communications director Sng Chern Hong said that the internet drug trade here is not yet a major problem for enforcement agencies, but that the bureau is concerned about it and is monitoring it closely.

Annual statistics from the bureau show that arrests across all ages for online purchases of drug and drug-related paraphernalia jumped nine-fold from 30 arrests in 2015 to 287 in 2020.

Last year’s case count is still small compared to the rest of the local drug market, contributing only around 10 per cent of the total 3,014 drug arrests reported by the bureau.

But it is the young addicts who go undetected that worry Mr Wilson Peh, a social worker who counsels and runs programmes for over 100 at-risk youths per year under charity organisation Youth Guidance Outreach Services (YGOS).

“What we’re seeing online is a free market for drugs that’s become very hard to regulate. All it takes is for someone to take a look inside, and they can enter,” said Mr Peh, who has worked at YGOS for five years.

“That’s what attracts the youths so much. They see how easy it is to get drugs, they see how they can do it all anonymously,” he said.

Another social worker, Mr Chan, who works at a local drug rehabilitation centre that houses up to 50 youths at a time, flagged online involvement in almost all of the cases he has seen there. He joined the centre a year ago, though he has worked closely with young drug abusers for seven years.

Mr Chan, who did not want to be fully named due to the sensitive nature of his job, said that young peddlers and addicts who are admitted to his centre conducted “almost all transactions” on messaging platforms WhatsApp and Telegram.

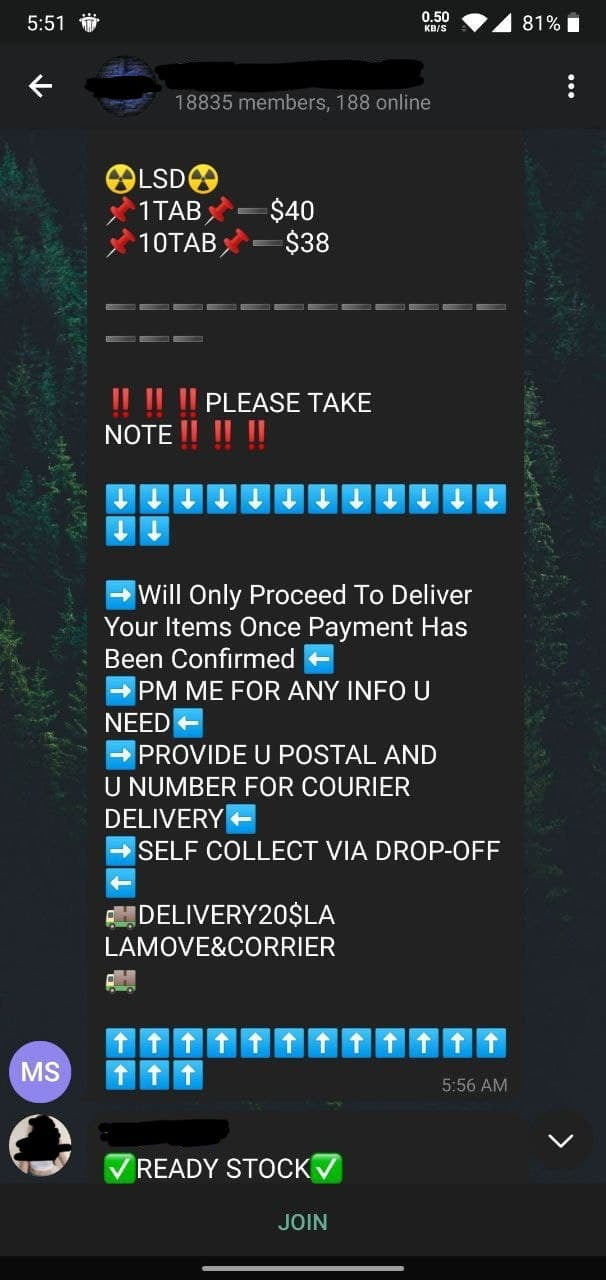

Telegram in particular has become a choice stronghold for black market dealings here, because of its encrypted platform and option for messages to self-destruct after 24 hours, leaving no trace of discussions.

Public chat groups on the app touting themselves as Singaporean contraband marketplaces offer meth, marijuana and synthetic drugs at S$30 to S$50 per order, with thousands of subscribers tuning in every day.

Mr Peh noted the use of Facebook’s Messenger service in one of his youth drug abuse cases.

A Secondary 2 student he counselled in 2018 was involved in a family business that used Facebook to contact networks of meth abusers. The boy’s parents and uncle would drive customers in a van to secluded areas like cemeteries or abandoned housing estates where they could consume meth, said Mr Peh.

“They would always change their names, like every week. They could just create a new account and approach people they knew or through referrals,” he said.

Notably, the proliferation of drugs on these platforms has brought the illegal market closer to everyday users, and removes the need for the dark web — a series of hidden networks that has become notorious for hosting illegal transactions.

Facebook, which also owns WhatsApp, responded to queries by pointing to its commerce policy. It specifies that the sale of drugs or drug-related paraphernalia is prohibited from its platforms and that the company may remove such listings or terminate perpetrators’ access to its services.

Telegram did not respond to requests for comment that were sent since February.

Mr Chan, works at a local drug rehab centre for youth

Once buyers connect to their sellers online, a variety of collection options are often available to them. Some peddlers on Telegram channels boast that doorstep deliveries are available through legitimate third-party courier services like Lalamove.

So far, Mr Chan has worked with two young dealers at his rehab centre who regularly used delivery services. One of them sold upwards of S$30,000 worth of drugs.

He said that by pushing illegal drug deliveries to legitimate platforms, dealers can ensure they never meet a buyer face-to-face.

“It’s going to get harder to catch these youths. The Government and social agencies like us are going to have to step up their game,” he added.

In response to queries, Lalamove wrote in a statement that it takes a “zero-tolerance approach” to the use of its service for illegal activities.

The statement added: “Those found to be engaging in illegal activity will face an immediate loss of access to the Lalamove app. In accordance with our terms and conditions and Singapore law, the transportation of dangerous and illegal goods and substances is strictly prohibited.”

“We will comply with any investigation by law enforcement to assist and prevent any such incidents from occurring.”

Lalamove also clarified that delivery drivers may cancel orders without penalty if they have concerns before or during the delivery, and report their concerns to the courier services and law enforcement.

CNB communications director Mr Sng said that the bureau has been monitoring the use of couriers to transport illegal drugs, and actively works with major courier operators. However, he declined to share details on operational methods.

“We’ve got to work closely on the ground, with members of the public. We do have some dispatch couriers who find packages are suspicious and they do inform us as well,” he said.

Mr Peh said that the drug market’s online shift has made youth work particularly challenging.

“The scary thing is that it’s become nearly impossible to identify these youths… It used to be easier to track kids in need of help. We could see them hanging out, the police could check on them,” he said.

Mr Joel Shashikumar, head of the Therapeutic Group Home at Boys’ Town, a charity for male youths under 25, said that social workers like him mostly rely on information shared by youngsters to learn about the movements of drug peddlers or crime syndicates on the web.

Only a handful of these teenagers are ever willing to open up, since most are afraid of implicating themselves and others, he said.

Though he started youth work nine years ago, it was only until 2015 that he began to see or hear of several teenagers buying drugs online.

The trend has been rising ever since, he added.

Increasingly, youth workers have also uncovered cases where parents are completely oblivious to their young teens discussing or networking to obtain drugs on the internet.

Mr Andy Leong, a youth worker at The Salvation Army’s Youth Development Centre, said it was extremely rare to meet parents who had a clue about their teen’s illegal online activities.

“The assumption is that they are playing with people, their friends. They feel like a game is a harmless thing,” he said.

“They don’t see that underneath that innocent surface, there’s a lot more brewing underneath.”

Mr Peh said: “The parents I meet in my case work, when they see a child using a phone, they think it means that the child is well-behaved. That’s quite bizarre to me. They used to tell me: ‘I know about my son and his friends’. But now they have no idea who their kids are hanging out with.”

Lai Jun Qi met several older teens online who asked him to join their secret society.

One of Mr Peh’s other major concerns is a lack of regulation in online mobile and computer gaming, which he has observed can be a segue into drugs and gang-related activity.

Gaming is a constant talking-point for youths who speak to him about their life issues, and several young teens under his care have been introduced to drugs while playing with strangers.

He recalled encountering lower-secondary school students exchanging contacts for dealers and locations to buy drugs, all over multiplayer voice chat. They used codewords to remain inconspicuous, he added.

“It’s very common for things to escalate in these cases… They meet someone online who they think is a good player, and they invite them for another match. From there, they can progress on to other activities.”

Dealers and gangsters are unlikely to intentionally play a game to bait younger teens, he admitted. Mobile gaming has risen in popularity over the last five years among young gang members and peddlers, mainly because they enjoy it just like other teens or young adults, he said.

But Mr Peh believes that this trend has given these sinister parties an opportunity to easily mix with a wider range of younger, more susceptible kids.

A youth he previously worked with, 17-year-old ITE student Lai Jun Qi, was introduced to a secret society through an online computer game when he was in Primary 6.

Several players he befriended online created a WhatsApp group to chat outside of the game, and eventually met in-person at a McDonald’s several months later.

There, two fellow group members — just a few years older than him — broached the subject of joining their gang.

“They said: ‘If someone bullies you, you all can get backup, fight like in the game. You won’t need to worry about anyone’,” said Jun Qi.

Most of the other boys expressed interest, but Jun Qi refused the offer, drawing ire from the older teens.

“I didn’t think it was worth it because I could go to jail. They said I was a ‘betrayer’ and they started sounding aggressive and standing up like they wanted to beat me,” he said.

He retreated home and avoided going out for an entire week out of fear that the gangsters would ambush him.

GAMING A GATEWAY TO DRUGS AND GANGS

Jun Qi plans to switch courses at his ITE college to study counselling. He hopes to one day work at YGOS, where he met Mr Peh.

Gang introductions like in Jun Qi’s case can be prevalent, said Mr Peh, a former secret society member himself. Recruitment used to be a selective process, but young gangsters nowadays rarely follow the rigid structure of past decades, he said.

For example, Jake*, 22, an ex-member of the Pak Hai Tong secret society, a gang infamous in the Boon Lay neighbourhood for slashing cases and fighting, said his old crime organisation is now more open to accepting unscreened recruits.

“We had a code. You needed to earn respect, let people know who you are, that you have something to offer. Now they are just letting anyone in, any punk,” said Jake, currently serving his national service.

When he was a gang fighter six years ago, recruitment through online gaming was practically non-existent. But last year, he heard of multiple cases where teens were invited to secret societies through popular mobile games.

And where there are gangs, there are usually drugs, according to convicted ex-dealer Mr Darren Tan, who in the 1990s and early 2000s peddled an average S$10,000 worth of illegal drug products a day.

“I’ve been in the game for the longest time, and gangs are invariably connected to drugs, whether for the profits or just for usage. It’s just in that community,” said Mr Tan, now a lawyer in his 40s under Invictus Law Corporation after his release from prison.

Mr Peh said some gangs may outwardly ban drugs among their ranks, but added that he has encountered many gangsters who broke their code in private.

“A lot of it is just talk. Drugs really exist on every level. The young ones, the old guard, all (gangsters) will be exposed to drugs,” he said.

Ex-gang associate Ron*, 18, said this link is still common even in street corner gangs today.

“I would see 13-year-olds high with the effects of meth. It was a common sight, never really surprised me,” said Ron, who was charged eight times for offences including rioting, mischief and money-laundering.

From 2018 to 2020, he roped more than 70 younger teenagers into his 800-strong network of secret society members, petty criminals and drug peddlers.

Ron linked around 70 younger boys with secret society members, drug peddlers and money launderers over two years. Online messaging and gaming were common in their network.

Ever since he was 16, he would befriend young teens he met on the street or through acquaintances — the same way he was brought into a life of crime when he was 14.

Then he would introduce them to his social circle, though at the time he thought it was merely a way to show off his connections.

Almost all of these boys later wound up in gangs or began taking hard drugs.

“The older ones would give the younger ones drugs to get them hooked, so they can sell more… The younger ones will look up to the older guys and think they are much cooler,” said Ron, now serving a probation while studying automotive technology at an ITE college.

“I basically ruined their lives.”

Though Ron is not an avid gamer himself, most of his peers or younger acquaintances in his network would regularly bond over mobile games.

“Everyone is gaming, everyone is using their phones. Most of us already communicated through Instagram before I left my social circle... I think you’ll start to see more and more of this,” he said.

YOUTH ORGANISATIONS FINDING THEIR FOOTING ONLINE

Meanwhile, social agencies are moving online in an attempt to build rapport with younger audiences. Several organisations launched social media accounts, like Boys’ Town’s outreach branch YouthReach, which started an Instagram account last year.

Others have started youth-targeted campaigns, such as last year’s HIGH campaign by the National Council Against Drug Abuse, which screened an interactive film about drug addiction at polytechnics and ITE colleges.

In February, CNB held a live virtual concert on its social media accounts featuring local artistes promoting anti-drug messages.

Mr Peh said that an online chat programme is being trialled at YGOS, his workplace.

“It doesn’t directly combat drugs, but the cyberworld has become so much louder over the years. We need to have some kind of presence in that world as a start,” he said.

He believes more needs to be done. For now, his best option for helping at-risk teenagers is to spend time with them, especially if it means using the same online platforms.

He makes a point to keep up with the latest mobile games to stay relevant with teens.

“The core problem remains. All of this is still crime, it’s against the law. The way that we are measuring it, the way that we are intervening may not be as effective as before,” he said.

"The whole problem has evolved to become more challenging. And we need to evolve with it."

The Youths of Generation High

Some of these youths were not featured in our story, but all of them shared with us their experiences with drugs and crime.

Hover over the buttons to learn more about them.

From left: Emmanuel Phua, Matthew Loh, Elgin Chong, Osmond Chia

MEET THE TEAM

We would like to thank

Our newsmakers for taking a leap of faith by believing in our project

Joshua and your family for trusting us with your stories and experiences

Wilson Peh for introducing us to the issue at hand and providing our project with its first building blocks

Our advisor, Ms Jessica Tan, for your guidance and encouragement throughout this journey

Ms Hedwig Alfred for your sharp advice

All text, pictures, illustrations and layouts, unless otherwise stated © 2021

All rights reserved.

First published in March 2021

Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information

Nanyang Technological University

31 Nanyang Link , Singapore 637718